Class:

- a social stratum sharing basic economic, political, or cultural characteristics, and having the same social position: Artisans form a distinct class in some societies.

-the system of dividing society; caste.

-social rank, esp. high rank.

-the members of a given group in society, regarded as a single entity.

Most people who are born onto any class stay within that class for life. Since I was born into a “middle class family, I will likely be middle class, unless I win the lottery or marry a very wealthy woman. (Both of which may happen at any moment.) The work that I do with clay/ceramics is tied to my history as a baker and a cook. It is also very much influenced by my having been raised in the country. I appreciate simple rustic things, and that is what I strive to create. These objects I make are meant to be in someone’s home or kitchen. I can imagine them living in a mansion, or castle, but they would likely be more at home in a small house or cottage. My work is made intentionally for any specific class. Since most of my friends and family are in the lower-middle class, this is where it ends up. I do not have any objection to people who create things for the upper class; it is just not what I do.

Then there is the polar opposite:

NEW YORK (AP) -- A sculpture of a stainless steel heart hanging from a golden bow sold Wednesday for $23.6 million, becoming the most expensive piece by a living artist ever auctioned, according to Sotheby's spokeswoman Lauren Gioia.

The bright magenta "Hanging Heart" sculpture is considered one of Jeff Koons' most important works.

The previous record for a living artist was Damien Hirst's "Lullaby Spring," which sold for $19.5 million at Sotheby's in London in June. Hirst's piece was a stainless steel cabinet containing 6,136 handcrafted and painted pills.

The Koons work was bought by the Gagosian Gallery, which had picked up his "Diamond [Blue]" sculpture for $11.8 million at a Christie's auction on Tuesday.

"Hanging Heart," nearly 9 feet tall and weighing more than 3,500 pounds, is from Koons' "Celebration" series, inspired by celebratory milestones such as birthdays and anniversaries. The "Diamond [Blue]" also is from the series.

"Koons is an artist who doesn't allow compromise, and 'Hanging Heart' is all about making an impossibility possible," said Tobias Meyer, head of Sotheby's contemporary art department.

The sculpture was offered for sale by a private American collector and had a pre-sale estimate of $15 million to $20 million. Its sale price included an auction house commission.

Friday, December 14, 2007

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

de Waal

Edmund de Waal - Ceramic Artist 1964-

Edmund de Waal was born in Nottingham, England in 1964. (4) He is considered to be one of the leading British potters of his generation. He has worked as a curator, a professor, a linguist and a lecturer. His studies and writings have made him an art critic and an art historian. Openings and spaces are continually studied and reinterpreted in his work. Edmund was raised in a clerical family, who attended church regularly. They lived near a few gothic cathedrals, and visited them and this is where Edmund was originally attracted to small spaces within larger architecture. When he was five, he asked for his father to take him to an evening class to learn how to make pots, and to throw. A small white pot, which he made, was the first pot he remembers liking. (2) From this age Edmund was already more attracted to minimalist work, than he was to busy, highly decorated objects.

Edmund then went to secondary school at the King’s School in Canterbury. There Geoffrey Whiting, who was one of the disciples of Bernard Leach, taught him pottery. (5) Whiting worked and taught very much in the Leach tradition, which brought together the East and the West by combining techniques and philosophies from Japan/China, and mediaeval English ceramics. Geoffrey Whiting believed very much in functional ceramics, and he taught Edmund in class and as his apprentice. By repetitively making pots, as a functional potter would, Edmund became more attuned to the slight differences in form. Edmund stated in an interview on BBC radio “… it’s a bit like doing scales as well – you’d never be surprised by a musician spending five years doing arpeggios, and there is a sense in a ceramic apprenticeship that that’s really what you’re doing.”

After Edmund graduated from secondary school he was sure that he wanted to become a potter. He continued as an apprentice for a couple years, and he undertook postgraduate studies in Japanese at Sheffield University. (4) He was awarded a Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Scholarship and worked at the Mejiro Ceramics Studio in Tokyo. He was brought up in a family of readers and writers, and though Edmund was immersed in ceramics he never stopped reading and writing. He then decided to attend Cambridge University, where he would study English. (2) Edmund is well known for his work with clay, but he is as well known for his writings. His books, which have been published, are:

Edmund de Waal Photography by Helene Binet Essays by Jorunn Veiteberg and Helen Waters Kettle's Yard / mima 2007

Rethinking Bernard Leach: Studio Pottery and Contemporary Ceramics (Japanese Edition) Shibunkaku Publishing Co. 2007

Twentieth Century Ceramics, Thames and Hudson, 2003

Design Sourcebook: Ceramics, New Holland Publishers, 1999 Dutch, German, American editions 1999 UK paperback edition 2003

Bernard Leach, Tate Publishing, 1998 new edition 1999, new edition 2003 Japanese edition 2006 with additional chapters

While Edmund studied English he continued to visit museums and galleries, such as the famous Kettle’s Yard. It was in these buildings that he began considering how his work could help re-design an interior space. Edmund was still dedicated to the idea that he would someday be a rural potter, and follow the Leach tradition. This meant that he would make “appropriate” work, which meant that he would make inexpensive domestic pottery with earth-like colors. In Geoffrey Whiting’s words, “Cheap enough to drop, part of everyone’s everyday life”, and this was Edmund’s mission statement. (2)

After finishing his studies at Cambridge University he set up a pottery studio in the countryside, on the Welsh borders, and then in Sheffield. Edmund was making functional stoneware vessels, and was still a potter who was very much influenced by the ideas and pots of Bernard Leach. Being aware of the “Anglo-Oriental” roots in his own work, he did not aspire to only continue the tradition. He had other influences, such as the work of early modernists and the Bauhaus movement. He had realized that he could critique the the Leach tradition intellectually while he was in Cambridge, and he began to do so. Leach was a very prolific writer, and potter as well. Bernard Leach wrote much of what Edmund had read about pottery and the union of the East and West. Edmund went back to Japan, and during this time he studied the local folk-craft, and the papers and journals of Leach. He noticed that Leach had actually not understood the language of Japanese, and that he only looked at certain forms. Edmund was finding “holes” in the studies, philosophies and writings of Leach. He decided to write about his findings, and this did not go over very well. Edmund found that the Leach tradition closes down opportunities for different kinds of work within ceramics. He found that

“...the great myth of Leach is that Leach is the great interlocutor for Japan and the East, the person who understood the East, who explained it to us all, brought out the mystery of the East. But in fact the people he was spending time with, and talking to, were very few, highly educated, often Western educated Japanese people, who in themselves had no particular contact with rural, unlettered Japan of peasant craftsman.” (2) These findings, and his writings gained him much criticism, as young Edmund had grown up within the Leach tradition.

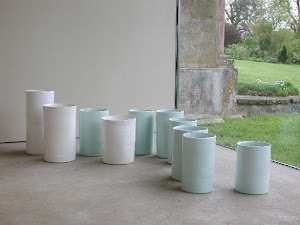

Edmund de Waal’s current work has moved away from single objects, and is more concerned with openings and spaces. He now works solely in high-fire porcelain, with celadon glazes. He believes that it is porcelain that is the matrix for the East and West, the Sung Dynasty and the Bauhaus. (1) Though there is much history to these colors and materials his work has an undeniable contemporary look and feel. By making large numbers of classic cylindrical and circular shapes, and using clean celadon glazes, Edmund’s work is very recognizable. This work has gained much international recognition. He has won the following awards:

2003 Silver Medal, World Ceramics Exposition, Korea

2000-2002 Leverhulme Special Research Fellowship

1998 British Council Award

1996 London Arts Board Individual Artists Award

1996 Fellow of Royal Society of Arts

1991-1993 Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation Scholarship

1985 Trinity Hall, Cambridge Scholarship

Edmund’s style has been labeled the height of minimalist chic, but his work speaks about more than just the forms and glazes. He experiments with how objects change a particular space, how they communicate with each other, and how much you even need to see of a pot for it to have an impact upon its surroundings. When asked if he felt his exploration of ceramics had become narrow with his choice of one type of clay and one type of glaze, he responded, “ I don’t think it’s narrow in the slightest. I think you can find breadth wherever you are.” (2) Edmund currently works and lives in London, where he shares a studio with Julian Stair, and his studio manager Marie Torbensdatter Hermann. He teaches at the University of Wesminster. His current artists statement is as follows:

I love the ‘visible imperfections’ that come from the gestures of throwing and handling clay and the fierce symmetries of industrial porcelain, the vessels of the chemical laboratory. My pots span both these histories. Working in Japan has given me a feeling for how pots can work in the hand, how their heft, balance and texture matters. So my pots are slightly bashed, slightly crooked and tell of their making.

For the last eight years I have also been making installation groups. I called them ‘cargoes’ of pots, an image that came from the images of sunken cargoes of porcelain.

There are few images of groups of porcelain – we are much more used to seeing single pieces in isolated splendour – and this has haunted me. Some of these installations were for Modernist houses as with my work at High Cross House in 1999. Some were for austere art galleries – as with the Porcelain Room made for the Geffrye Museum, 2002-2003 and shown at the Kunstindustri Museum in Copenhagen in 2004. For my solo show at Roche Court in 2004 I made three installations that respond to the Arcadian landscape in which the gallery sits. This focus on installation has allowed me to be ambitious in making pots that challenge architectural space. My installation groups focus on the ways in which subtle modulations are manifested through repetition.

Recent projects at Blackwell, the Lake District mansion designed by Baillie Scott and at the National Museum and Gallery, Wales have extended this practice.

Much of my recent work explores colour through hidden interstices and openings. These pieces look at how colour change through shadow.

All these pots were made in porcelain as I believe that it is the porcelain that is the matrix for East and West, the sung dynasty and the Bauhaus.

It remains to be a powerfully contemporary medium.

Bibliography

(1) Twentieth Century Ceramics, Thames and Hudson, 2003

(2) www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/johntusainterview/dewaal_transcript.shtml-69k-

(3) www.edmunddewaal.com

(4) collection.britishcouncil.org/html/artist.aspx?id=18077-13k

(5) Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 54. 2003

Edmund de Waal was born in Nottingham, England in 1964. (4) He is considered to be one of the leading British potters of his generation. He has worked as a curator, a professor, a linguist and a lecturer. His studies and writings have made him an art critic and an art historian. Openings and spaces are continually studied and reinterpreted in his work. Edmund was raised in a clerical family, who attended church regularly. They lived near a few gothic cathedrals, and visited them and this is where Edmund was originally attracted to small spaces within larger architecture. When he was five, he asked for his father to take him to an evening class to learn how to make pots, and to throw. A small white pot, which he made, was the first pot he remembers liking. (2) From this age Edmund was already more attracted to minimalist work, than he was to busy, highly decorated objects.

Edmund then went to secondary school at the King’s School in Canterbury. There Geoffrey Whiting, who was one of the disciples of Bernard Leach, taught him pottery. (5) Whiting worked and taught very much in the Leach tradition, which brought together the East and the West by combining techniques and philosophies from Japan/China, and mediaeval English ceramics. Geoffrey Whiting believed very much in functional ceramics, and he taught Edmund in class and as his apprentice. By repetitively making pots, as a functional potter would, Edmund became more attuned to the slight differences in form. Edmund stated in an interview on BBC radio “… it’s a bit like doing scales as well – you’d never be surprised by a musician spending five years doing arpeggios, and there is a sense in a ceramic apprenticeship that that’s really what you’re doing.”

After Edmund graduated from secondary school he was sure that he wanted to become a potter. He continued as an apprentice for a couple years, and he undertook postgraduate studies in Japanese at Sheffield University. (4) He was awarded a Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Scholarship and worked at the Mejiro Ceramics Studio in Tokyo. He was brought up in a family of readers and writers, and though Edmund was immersed in ceramics he never stopped reading and writing. He then decided to attend Cambridge University, where he would study English. (2) Edmund is well known for his work with clay, but he is as well known for his writings. His books, which have been published, are:

Edmund de Waal Photography by Helene Binet Essays by Jorunn Veiteberg and Helen Waters Kettle's Yard / mima 2007

Rethinking Bernard Leach: Studio Pottery and Contemporary Ceramics (Japanese Edition) Shibunkaku Publishing Co. 2007

Twentieth Century Ceramics, Thames and Hudson, 2003

Design Sourcebook: Ceramics, New Holland Publishers, 1999 Dutch, German, American editions 1999 UK paperback edition 2003

Bernard Leach, Tate Publishing, 1998 new edition 1999, new edition 2003 Japanese edition 2006 with additional chapters

While Edmund studied English he continued to visit museums and galleries, such as the famous Kettle’s Yard. It was in these buildings that he began considering how his work could help re-design an interior space. Edmund was still dedicated to the idea that he would someday be a rural potter, and follow the Leach tradition. This meant that he would make “appropriate” work, which meant that he would make inexpensive domestic pottery with earth-like colors. In Geoffrey Whiting’s words, “Cheap enough to drop, part of everyone’s everyday life”, and this was Edmund’s mission statement. (2)

After finishing his studies at Cambridge University he set up a pottery studio in the countryside, on the Welsh borders, and then in Sheffield. Edmund was making functional stoneware vessels, and was still a potter who was very much influenced by the ideas and pots of Bernard Leach. Being aware of the “Anglo-Oriental” roots in his own work, he did not aspire to only continue the tradition. He had other influences, such as the work of early modernists and the Bauhaus movement. He had realized that he could critique the the Leach tradition intellectually while he was in Cambridge, and he began to do so. Leach was a very prolific writer, and potter as well. Bernard Leach wrote much of what Edmund had read about pottery and the union of the East and West. Edmund went back to Japan, and during this time he studied the local folk-craft, and the papers and journals of Leach. He noticed that Leach had actually not understood the language of Japanese, and that he only looked at certain forms. Edmund was finding “holes” in the studies, philosophies and writings of Leach. He decided to write about his findings, and this did not go over very well. Edmund found that the Leach tradition closes down opportunities for different kinds of work within ceramics. He found that

“...the great myth of Leach is that Leach is the great interlocutor for Japan and the East, the person who understood the East, who explained it to us all, brought out the mystery of the East. But in fact the people he was spending time with, and talking to, were very few, highly educated, often Western educated Japanese people, who in themselves had no particular contact with rural, unlettered Japan of peasant craftsman.” (2) These findings, and his writings gained him much criticism, as young Edmund had grown up within the Leach tradition.

Edmund de Waal’s current work has moved away from single objects, and is more concerned with openings and spaces. He now works solely in high-fire porcelain, with celadon glazes. He believes that it is porcelain that is the matrix for the East and West, the Sung Dynasty and the Bauhaus. (1) Though there is much history to these colors and materials his work has an undeniable contemporary look and feel. By making large numbers of classic cylindrical and circular shapes, and using clean celadon glazes, Edmund’s work is very recognizable. This work has gained much international recognition. He has won the following awards:

2003 Silver Medal, World Ceramics Exposition, Korea

2000-2002 Leverhulme Special Research Fellowship

1998 British Council Award

1996 London Arts Board Individual Artists Award

1996 Fellow of Royal Society of Arts

1991-1993 Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation Scholarship

1985 Trinity Hall, Cambridge Scholarship

Edmund’s style has been labeled the height of minimalist chic, but his work speaks about more than just the forms and glazes. He experiments with how objects change a particular space, how they communicate with each other, and how much you even need to see of a pot for it to have an impact upon its surroundings. When asked if he felt his exploration of ceramics had become narrow with his choice of one type of clay and one type of glaze, he responded, “ I don’t think it’s narrow in the slightest. I think you can find breadth wherever you are.” (2) Edmund currently works and lives in London, where he shares a studio with Julian Stair, and his studio manager Marie Torbensdatter Hermann. He teaches at the University of Wesminster. His current artists statement is as follows:

I love the ‘visible imperfections’ that come from the gestures of throwing and handling clay and the fierce symmetries of industrial porcelain, the vessels of the chemical laboratory. My pots span both these histories. Working in Japan has given me a feeling for how pots can work in the hand, how their heft, balance and texture matters. So my pots are slightly bashed, slightly crooked and tell of their making.

For the last eight years I have also been making installation groups. I called them ‘cargoes’ of pots, an image that came from the images of sunken cargoes of porcelain.

There are few images of groups of porcelain – we are much more used to seeing single pieces in isolated splendour – and this has haunted me. Some of these installations were for Modernist houses as with my work at High Cross House in 1999. Some were for austere art galleries – as with the Porcelain Room made for the Geffrye Museum, 2002-2003 and shown at the Kunstindustri Museum in Copenhagen in 2004. For my solo show at Roche Court in 2004 I made three installations that respond to the Arcadian landscape in which the gallery sits. This focus on installation has allowed me to be ambitious in making pots that challenge architectural space. My installation groups focus on the ways in which subtle modulations are manifested through repetition.

Recent projects at Blackwell, the Lake District mansion designed by Baillie Scott and at the National Museum and Gallery, Wales have extended this practice.

Much of my recent work explores colour through hidden interstices and openings. These pieces look at how colour change through shadow.

All these pots were made in porcelain as I believe that it is the porcelain that is the matrix for East and West, the sung dynasty and the Bauhaus.

It remains to be a powerfully contemporary medium.

Bibliography

(1) Twentieth Century Ceramics, Thames and Hudson, 2003

(2) www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/johntusainterview/dewaal_transcript.shtml-69k-

(3) www.edmunddewaal.com

(4) collection.britishcouncil.org/html/artist.aspx?id=18077-13k

(5) Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 54. 2003

Tuesday, December 4, 2007

ocarina

oc·a·ri·na (ŏk'ə-rē'nə)

n. A small terra-cotta or plastic wind instrument with finger holes, a mouthpiece, and an elongated ovoid shape.

[Italian, from dialectal ucarenna, diminutive of Italian oca, goose (from the fact that its mouthpiece is shaped like a goose's beak), from Vulgar Latin *auca, from *avica, from Latin avis, bird; see awi- in Indo-European roots.]

Decorated with figures in ceremonial dress and various animal effigies, clay ocarinas were a standard part of ceremonial life in pre-Columbian Central America. Made with a varying number of tone holes and in different sizes, ocarinas could imitate the calls of small birds as well as the resonant hoots of owls. Photo by Roger Hamilton—IDB.

The object I chose to look at in more detail was a small Pre-Columbian ceramic whistle. This was made in Peru, and was made inland, though it is in the shape of a shell. It is about 2” / 3” wide, and it was burnished and slip decorated. Like other Pre-Columbian vessels, it is unglazed and probably pit-fired. The animist culture in which this was made had great respect for the natural world, and this is apparent in their vessels for ceremony as well as those for everyday use. Respect for the ocean, as a metaphor for life, as a great source of food and weather, is apparent in their decorations and choice of forms. These simple forms, mimicking seashells, have a peaceful feeling to them. I am not sure exactly what they were used for, but they are said to have precise tones, possibly for specific people, times of the year, or for specific ceremonies. These were surely made after people had made similar whistles out of real shells. The people further from the ocean probably had a harder time getting objects from the ocean, but this did not hinder their desire to have such objects, they just made them out of clay. They also made many other sea forms, of other shells, fish, shellfish, and mammals. It is not hard for me to imagine a culture that was connected to nature in a way that our culture is not. Pre-Columbus, and Pre-Christ humans were generally more connected to the earth and its other inhabitants. People also thought of things cyclically, as the seasons cycle through time, as apposed to a more linear view of the world that was created primarily through Christianity. There are contemporary equivalents to such objects, but I have never seen or heard of them being used ceremonially today. The Pre-Columbian objects are worth quite a lot today, as they are “artifacts” from a past culture. I would love to have a small Pre-Columbian object. I had an attraction to these wares/objects long before I began working with clay myself. The relationship to the human body is obvious, it was made to be picked up and blown through.

n. A small terra-cotta or plastic wind instrument with finger holes, a mouthpiece, and an elongated ovoid shape.

[Italian, from dialectal ucarenna, diminutive of Italian oca, goose (from the fact that its mouthpiece is shaped like a goose's beak), from Vulgar Latin *auca, from *avica, from Latin avis, bird; see awi- in Indo-European roots.]

Decorated with figures in ceremonial dress and various animal effigies, clay ocarinas were a standard part of ceremonial life in pre-Columbian Central America. Made with a varying number of tone holes and in different sizes, ocarinas could imitate the calls of small birds as well as the resonant hoots of owls. Photo by Roger Hamilton—IDB.

The object I chose to look at in more detail was a small Pre-Columbian ceramic whistle. This was made in Peru, and was made inland, though it is in the shape of a shell. It is about 2” / 3” wide, and it was burnished and slip decorated. Like other Pre-Columbian vessels, it is unglazed and probably pit-fired. The animist culture in which this was made had great respect for the natural world, and this is apparent in their vessels for ceremony as well as those for everyday use. Respect for the ocean, as a metaphor for life, as a great source of food and weather, is apparent in their decorations and choice of forms. These simple forms, mimicking seashells, have a peaceful feeling to them. I am not sure exactly what they were used for, but they are said to have precise tones, possibly for specific people, times of the year, or for specific ceremonies. These were surely made after people had made similar whistles out of real shells. The people further from the ocean probably had a harder time getting objects from the ocean, but this did not hinder their desire to have such objects, they just made them out of clay. They also made many other sea forms, of other shells, fish, shellfish, and mammals. It is not hard for me to imagine a culture that was connected to nature in a way that our culture is not. Pre-Columbus, and Pre-Christ humans were generally more connected to the earth and its other inhabitants. People also thought of things cyclically, as the seasons cycle through time, as apposed to a more linear view of the world that was created primarily through Christianity. There are contemporary equivalents to such objects, but I have never seen or heard of them being used ceremonially today. The Pre-Columbian objects are worth quite a lot today, as they are “artifacts” from a past culture. I would love to have a small Pre-Columbian object. I had an attraction to these wares/objects long before I began working with clay myself. The relationship to the human body is obvious, it was made to be picked up and blown through.

Wednesday, November 7, 2007

Karen Karnes

Karen Karnes was born in 1925 in New York City. She was raised there, where she attended art schools for children. Her parents were Russian and Polish immigrants who were garment workers and were proud communists. Karen was influenced in many ways by her parent’s philosophies, as she always has respected working in small communities. Karen applied and was accepted to the ritzy La Guardia Art School as a high school student. As a child she was surrounded by urban realities and visual influences, but it seems her parent’s old-world ideals kept her grounded. Karnes today makes more contemporary vessels, which are given different attention to design than her original pottery.

After high school Karen went to Brooklyn College because she wanted to continue her artwork, and be close to home. At the time she was primarily painting and printmaking. Her college sweetheart, David Weinrib, brought her a flower on their first date, and then brought her a lump of clay one of the following days. David had already been up-state where he studied glaze treatments and worked in clay at Alfred University. Their romance led to love, and they decided to leave New York to travel and study. They went to Italy together where they were both overcome by the art of Europe. Karen said that she was especially drawn to the classical Italian forms and the painted glaze techniques. She still today makes many traditional forms, which I believe show how she was impressed by these forms, and in a way still pays homage to them. Today Karen primarily fills her kilns with more contemporary forms, but she continues to produce casseroles, teapots, cups and bowls.

When Karen was in her mid-twenties, she and David decided to move down to North Carolina to attend/work at the Black Mountain College. Karen fell in love with the simplicity of life in the country. Though they were poor, and selling pots to make enough money for food, they had no desire to return to the city. She has stated that what she looked at as a child, including buildings, are visual influences in her work. When she was living in North Carolina she was living with a talented group of people. This group of musicians, philosophers and artists had great parties and discussions at their farm-house. As a group they seemed very interested in stretching the limits of Modernism; working to further the ideas and practices of the Dada and Bauhaus movements. One of her friends at the Black Mountain College was Merce Cunningham, for she lived with his partner John Cage. These two were impressed with Zen Buddhist thought, and were intrigued by what chance had to do with an outcome. They expressed this in their compositions and choreography, in music and dance. “Nichi, nichi kore ko kore.” Every day is a good Day, a Zen Buddhist saying, was one they as a group enjoyed reminding each other of.

The time in the Carolinas was when Karen Karnes became what she wanted to be, a country potter. She was introduced to potters such as Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, and local Americans Malcom Davis and Mark Shapiro. She never felt as if she was part of the “Leach Movement”, but she definitely had respect for the work and ideas of Leach and Hamada. Karen decided to live the rest of her life on a farm, working with clay and using old firing practices such as wood and salt firing. She had a disastrous experience a few years ago when her house and studio burned to the ground because of a kiln fire. Karen received many generous donations from a large pottery sale, to help her re-build her country house and studio. Potters from across the globe showed their respect and love by donating works for this cause. Karen received a Graduate Fellowship from Alfred University, and more recently won a gold medal for the consummate craftsmanship from The American Craft Council. Her work is displayed in numerous galleries and permanent collections worldwide.

Bibliography

“Interview with Karen Karnes.” Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Aug. 9-10, 2005

http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/karnes05.htm

“Ceramics, Sculpture and Contemporary Art.” Ferrin Gallery, 2006

http://ferringallery.com/dynamic/artist_bio.asp?artistID=33

After high school Karen went to Brooklyn College because she wanted to continue her artwork, and be close to home. At the time she was primarily painting and printmaking. Her college sweetheart, David Weinrib, brought her a flower on their first date, and then brought her a lump of clay one of the following days. David had already been up-state where he studied glaze treatments and worked in clay at Alfred University. Their romance led to love, and they decided to leave New York to travel and study. They went to Italy together where they were both overcome by the art of Europe. Karen said that she was especially drawn to the classical Italian forms and the painted glaze techniques. She still today makes many traditional forms, which I believe show how she was impressed by these forms, and in a way still pays homage to them. Today Karen primarily fills her kilns with more contemporary forms, but she continues to produce casseroles, teapots, cups and bowls.

When Karen was in her mid-twenties, she and David decided to move down to North Carolina to attend/work at the Black Mountain College. Karen fell in love with the simplicity of life in the country. Though they were poor, and selling pots to make enough money for food, they had no desire to return to the city. She has stated that what she looked at as a child, including buildings, are visual influences in her work. When she was living in North Carolina she was living with a talented group of people. This group of musicians, philosophers and artists had great parties and discussions at their farm-house. As a group they seemed very interested in stretching the limits of Modernism; working to further the ideas and practices of the Dada and Bauhaus movements. One of her friends at the Black Mountain College was Merce Cunningham, for she lived with his partner John Cage. These two were impressed with Zen Buddhist thought, and were intrigued by what chance had to do with an outcome. They expressed this in their compositions and choreography, in music and dance. “Nichi, nichi kore ko kore.” Every day is a good Day, a Zen Buddhist saying, was one they as a group enjoyed reminding each other of.

The time in the Carolinas was when Karen Karnes became what she wanted to be, a country potter. She was introduced to potters such as Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, and local Americans Malcom Davis and Mark Shapiro. She never felt as if she was part of the “Leach Movement”, but she definitely had respect for the work and ideas of Leach and Hamada. Karen decided to live the rest of her life on a farm, working with clay and using old firing practices such as wood and salt firing. She had a disastrous experience a few years ago when her house and studio burned to the ground because of a kiln fire. Karen received many generous donations from a large pottery sale, to help her re-build her country house and studio. Potters from across the globe showed their respect and love by donating works for this cause. Karen received a Graduate Fellowship from Alfred University, and more recently won a gold medal for the consummate craftsmanship from The American Craft Council. Her work is displayed in numerous galleries and permanent collections worldwide.

Bibliography

“Interview with Karen Karnes.” Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Aug. 9-10, 2005

http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/karnes05.htm

“Ceramics, Sculpture and Contemporary Art.” Ferrin Gallery, 2006

http://ferringallery.com/dynamic/artist_bio.asp?artistID=33

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Jane Reumert

'''Jane Reumert'''

Jane Reumert was born in Denmark in 1942. Reumert has spent more than 40 years as a professional studio ceramist. She is one of Denmark’s most respected artists, and she has gained much international recognition. She began as many potters do working with stoneware clay, and making functional pottery. http://www.pulsceramics.com Over the course of her career, her dedication to the process and the material has given her an understanding and touch that is skilled and unique. In other professions, her tireless testing and questioning would most likely be called research. People in the visual-arts world do not usually consider their artwork to be research, but I it is hard to call her relentless investigation anything else.

Jane made changes to her work as it developed and matured into what it is today, though she has always sought to make vessels which were simple, and close to nature. Reumert’s work has many influences, but nature and calligraphy are “deep-rooted sources of inspiration”. In an interview she stated that as a child she was captivated with nature, with birds – and their nests, feathers and eggs. This acute observation of nature, especially of birds, is shown clearly in some of her more contemporary works that mimic eggs and feathers of birds. Bodil Busk Laurensen, "Jane Reumert's Fidelity to Ceramics," Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 62, 2005, pp. 20-24. She has also mastered the art of calligraphy, and uses lettering styles from the East to the West.

After working on throwing and glazing techniques for more than thirty years her thoughts and practices took an interesting turn. She began to strive for translucency, and thin, refined beauty. In the late 1980’s she began working in porcelain clay, which can be translucent when it is thin and fired to very high temperatures. She began making paper-thin vessels, salt glazed, and fired to 1330 degrees Celsius (above 2300 F). In the early 1990s she began experimenting with the addition of fiberglass and other fibers added to her clay body, which enabled her to construct even thinner and bigger translucent forms. Her “eggshell” and “feather” vessels are so thin and light they seem to be from another world. She often displays her work on wire tripods, so the vessels appear to be floating above their shadows.http://www.pulsceramics.com Reumert’s work is a great metaphor of the fragility of our existence.

She has shown internationally, and has been awarded prizes for her work. Among these, in 1994, she was awarded Scandinavia’s most prestigious design prize: the Torsten and Wanja Soderberg Nordic Design Prize.Bodil Busk Laurensen, "Jane Reumert's Fidelity to Ceramics," Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 62, 2005, pp. 20-24. Reumert has published writings and books on ceramic techniques, as well as on her own work. She writes in Danish, but some of her books have been translated into other languages. Examples of these are her two books, Transparency, and Contemporary Pottery. Recently Reumert has moved away from her home and studio on the island of Bornholm. She is now living and working close to Copenhagen. She is now using a wood-fired kiln, and has chosen to change from salt firings to soda firings, which are a bit more environmentally friendly. http:pulsceramics.com Just this past summer she took part in the Nordic Woodfire Marathon, and was a guest artist at the International Ceramic Research Center in Denmark.http:woodfiremarathon2007.blogspot.com

Links:

http://www.carlakoch.nl/

http://www.carlakoch.nl/kunstenaars/jreumert.html - images

http://www.ceramic.dk/

References:

Bodil Busk Laurensen, “Jane Reumert’s Fidelity to Ceramics,” ''Ceramics: Art and Perception'', No. 62, 2005, pp. 20-24.

http://woodfiremarathon2007.blogspot.com/

http://www.pulsceramics.com/janereumert.html

Jane Reumert was born in Denmark in 1942. Reumert has spent more than 40 years as a professional studio ceramist. She is one of Denmark’s most respected artists, and she has gained much international recognition. She began as many potters do working with stoneware clay, and making functional pottery. http://www.pulsceramics.com Over the course of her career, her dedication to the process and the material has given her an understanding and touch that is skilled and unique. In other professions, her tireless testing and questioning would most likely be called research. People in the visual-arts world do not usually consider their artwork to be research, but I it is hard to call her relentless investigation anything else.

Jane made changes to her work as it developed and matured into what it is today, though she has always sought to make vessels which were simple, and close to nature. Reumert’s work has many influences, but nature and calligraphy are “deep-rooted sources of inspiration”. In an interview she stated that as a child she was captivated with nature, with birds – and their nests, feathers and eggs. This acute observation of nature, especially of birds, is shown clearly in some of her more contemporary works that mimic eggs and feathers of birds. Bodil Busk Laurensen, "Jane Reumert's Fidelity to Ceramics," Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 62, 2005, pp. 20-24. She has also mastered the art of calligraphy, and uses lettering styles from the East to the West.

After working on throwing and glazing techniques for more than thirty years her thoughts and practices took an interesting turn. She began to strive for translucency, and thin, refined beauty. In the late 1980’s she began working in porcelain clay, which can be translucent when it is thin and fired to very high temperatures. She began making paper-thin vessels, salt glazed, and fired to 1330 degrees Celsius (above 2300 F). In the early 1990s she began experimenting with the addition of fiberglass and other fibers added to her clay body, which enabled her to construct even thinner and bigger translucent forms. Her “eggshell” and “feather” vessels are so thin and light they seem to be from another world. She often displays her work on wire tripods, so the vessels appear to be floating above their shadows.http://www.pulsceramics.com Reumert’s work is a great metaphor of the fragility of our existence.

She has shown internationally, and has been awarded prizes for her work. Among these, in 1994, she was awarded Scandinavia’s most prestigious design prize: the Torsten and Wanja Soderberg Nordic Design Prize.Bodil Busk Laurensen, "Jane Reumert's Fidelity to Ceramics," Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 62, 2005, pp. 20-24. Reumert has published writings and books on ceramic techniques, as well as on her own work. She writes in Danish, but some of her books have been translated into other languages. Examples of these are her two books, Transparency, and Contemporary Pottery. Recently Reumert has moved away from her home and studio on the island of Bornholm. She is now living and working close to Copenhagen. She is now using a wood-fired kiln, and has chosen to change from salt firings to soda firings, which are a bit more environmentally friendly. http:pulsceramics.com Just this past summer she took part in the Nordic Woodfire Marathon, and was a guest artist at the International Ceramic Research Center in Denmark.http:woodfiremarathon2007.blogspot.com

Links:

http://www.carlakoch.nl/

http://www.carlakoch.nl/kunstenaars/jreumert.html - images

http://www.ceramic.dk/

References:

Bodil Busk Laurensen, “Jane Reumert’s Fidelity to Ceramics,” ''Ceramics: Art and Perception'', No. 62, 2005, pp. 20-24.

http://woodfiremarathon2007.blogspot.com/

http://www.pulsceramics.com/janereumert.html

Wednesday, October 24, 2007

the way of tea

To witness the Tea Ceremony, even if it was an instructional version, was wonderful. I respect how even in contemporary Japanese culture people are connected to tradition. The ceramic vessel has been used and admired in everyday life in Japan for thousands of years. The Tea Ceremony is a codified practice, which has evolved throughout the centuries, but it still hold true to the original intentions of the Zen monks. I like that people are continuing to practice the Ceremony, with the idea that it spreads peace. I have read very little about Zen Buddhism, but I understand that there are different levels of enlightenment, and that there are different ways to attain enlightenment as well. I believe that Zen Buddhists find peace and understanding by taking part in this ceremony. This is not hard for me to imagine, as I felt similar feelings by simply observing one. Here we are in the month that is considered to be the most “wabi”, October. The understanding that beauty is not on the outside, that imperfections and deformities can be the very things that make something special, and that we are all connected to everything else all realizations that one needs to attain in order to become “enlightened”. The Tea Ceremony seems to assure that the people who take part in it, observe or ponder these thoughts. I love how every move seemed to be intentional, yet without thought. If the practice became something that could be done without thought I believe it could be closer to a means of meditation, which it most likely is to many. The four main aspects were: Harmony, Respect, Purity and Tranquility. It is hard to dislike this list. I feel a connection to a practice that elevates a food and drinking experience to such a degree. It is special to see that part of the ceremony, after the guests drink tea, they are expected to take a moment to admire the ceramic vessels from which they had just drank the “macha” tea. The Tea Ceremony, and all of its traditions have changes through the ages. It is nice that the Buddhists came to admire less perfected forms, like those from rural Korea. Their deep understanding of themselves, and their relationship to the universe makes it much easier for me to accept that they are on to something. I would like to go to Japan one day, and to witness a tea ceremony in a temple. It is not easy for me to write about how this can or will influence my ceramic work in the future. I can say that I think that I would like to become a potter who is less concerned with being contemporary, and one who meditates.

Tuesday, October 16, 2007

Snap Cups

Angela Schwab, a local artist and Cu graduate, visited our advanced ceramics class in Boulder this week. She took some time to explain her work, and her recent accomplishments. Most relevant to out class was her explanation of how her blog, and internet activity has helped her on her way. Her blog site is: blog.invaltdesign.com . She stated that she spends hours each day reading and writing on blogs. Angela spoke of how important online communication is today, and that though it is not necessary for one to take part in the online world, it can jumpstart one’s career. People from all countries can look at one’s work, comment on it, buy it, sell it, trade it – and eventually spread the word about it. Some interesting sites Angela suggested looking at are:

www.etsy.com – craft and independent design (like e-bay)

SAC – society of arts and crafts w/ cup show at Christmas www.designboom.com – contemporary design site

(has competition “Dining in 2015”.)

Handled with Care – show and comp. in England

www.joshspear.com - CU drop-out, Blog promoter

www.etsy.com – craft and independent design (like e-bay)

SAC – society of arts and crafts w/ cup show at Christmas www.designboom.com – contemporary design site

(has competition “Dining in 2015”.)

Handled with Care – show and comp. in England

www.joshspear.com - CU drop-out, Blog promoter

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)